The Surge (V) - The Trainspotter

Three years prior to its unveiling, and a decade after Renault’s design transformation had been set in motion, the actual design process of the Renault Mégane MkII is ready to begin; Patrick le Quément reminisces, with some assistance, courtesy of Christopher Butt

In 1999, with new processes in place and a concept car, as well as a production model having paved the way, the stage was finally set for the actual creation of Mégane II.

Trainspotting of the kind I’m referring to here has nothing to do with the 100.000 or so anorak-clad individuals who spend their time hanging around on the end of platforms at British railway stations, writing down the numbers of passing trains as a hobby. It does, however, concern those whose passion for cars is all-consuming, who truly excel themselves if they also happen to be highly talented designers. Stéphan Barral falls into that rarefied category. After all, he is known to spend part of his summer vacations in Northern Sweden, near the town of Kiruna; anorak-clad, photographing camouflaged prototypes.

Car design is a team effort first and foremost. Yet any team can only ever be as good as its members, some of which play more significant roles than others. Accordingly, despite all that groundwork having been carried out over the course of more than a decade, regardless of those previous, highly influential concept cars, the role of the designers eventually tasked with creating Mégane II is not to be underestimated.

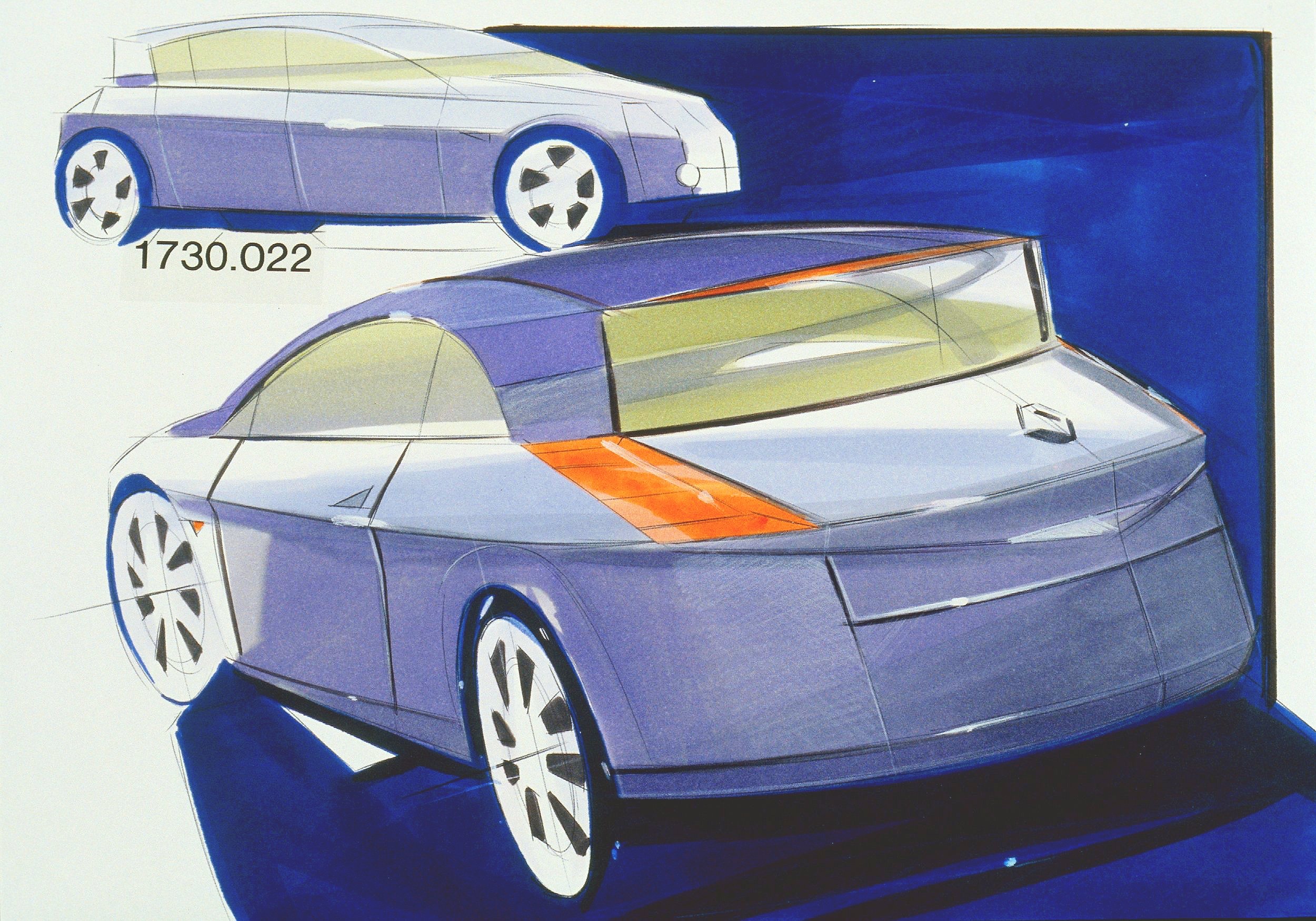

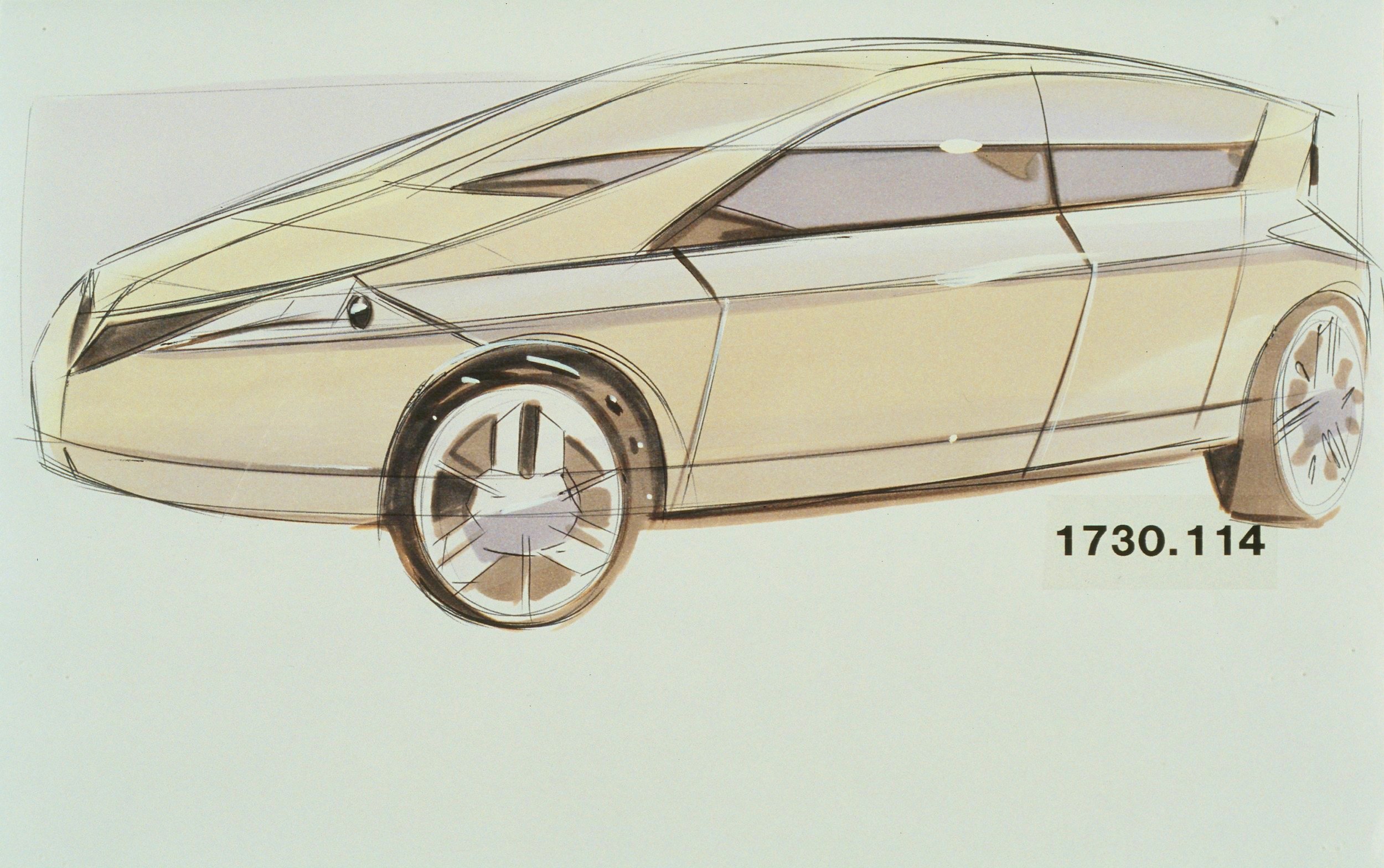

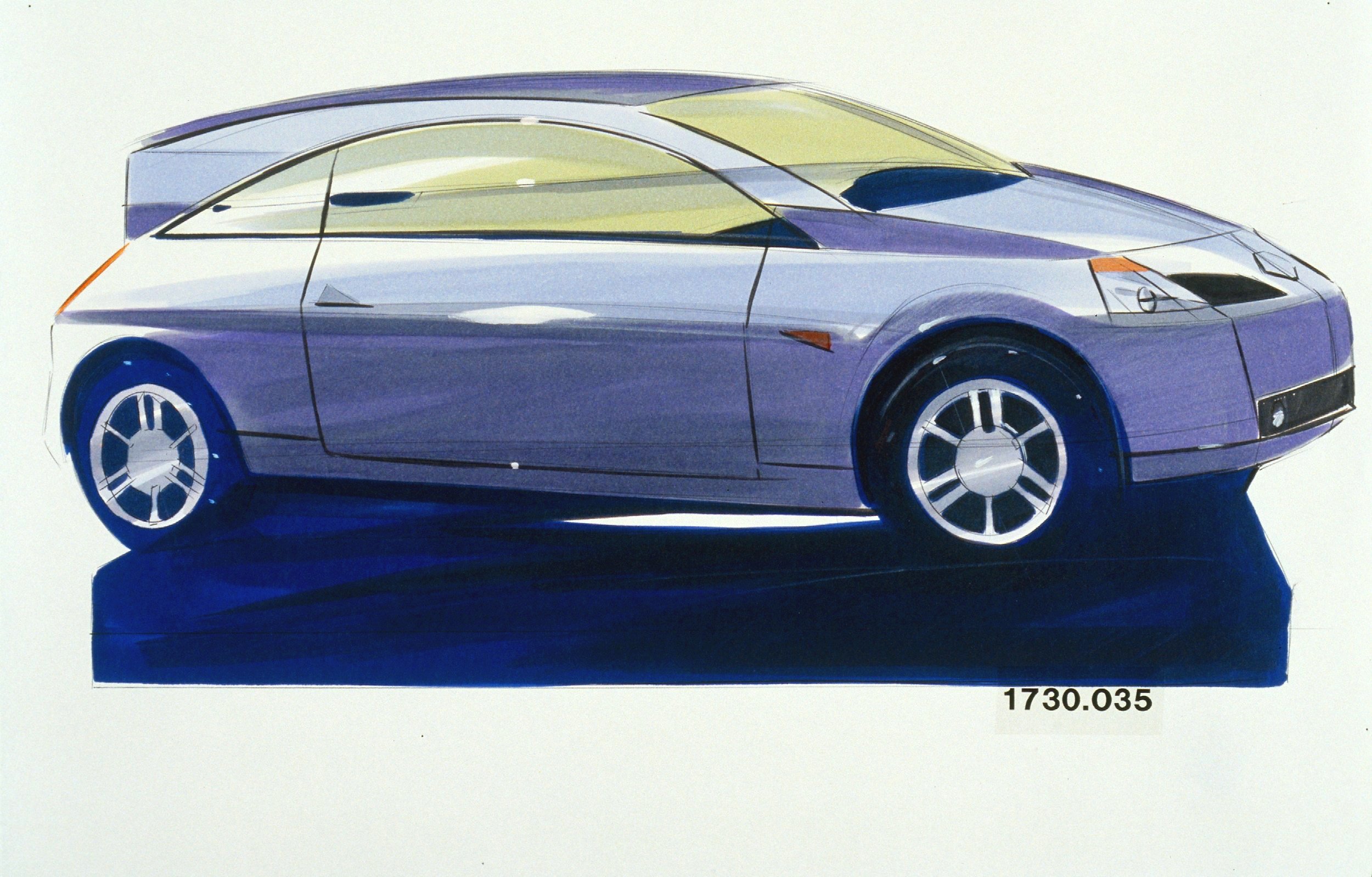

Stéphan and seven other designers took part in the exterior design competition for the second generation Mégane, of which three exterior themes were selected. Stéphan, the author of the head-turning Mégane II as we know it today, received the most number of votes on his proposal. He was at the time a 23-year-old, fervent designer, born in Montpellier and thus speaking with the typically melodious accent of that part of France, which can still be detected and enjoyed 27 years later. As though it was yesterday, I still remember his radiant smile, when he measured how much his design had carried the day with the internal Design selection committee, as there must have been at least one third more red dots positioned on his design proposal than any other. That smile has never left him since.

The modelling of the three proposals still in the running began, with the one by François Leboine sporting a somewhat conventional, yet well-balanced rear end, associated with a front end design that was appealing, but stretched beyond the frontier of our corporate identity. David Durand’s theme displayed a rather «active» and most interesting bodyside sculpting, which quietened down at either extremity. As for Stéphan’s, we agreed that we would only alter what would improve the concentrated core of the design theme, but would not make compromises with the devil - even at the risk of some being led to believe that we might be wicked. Again and again, I had shared with Stéphan my theory on automobile design: not to strive for perfect balance, but rather aim at perfect imbalance. The silhouette looked very much like what French design diva, Andrée Putman, had written on the Vel Satis concept car: «It looks like one of those street heroes wearing a basketball cap, back to front.»

Stéphan worked with a particularly accomplished clay modeller named Philippe Alves, and they used their tuning fork to achieve the perfect tone for the overall composition. The body side surfaces were full-yet-taut, enhanced by a character line that converged in a downward accent at the rear of the model. We succeeded at retaining the almost flush body-to-rear bumper offset by filing an innovative patent, which contributed so much to give an integrated look to the silhouette. But the car’s design did not limit itself to its unique rear end; much fine tuning was undertaken to contribute to the making of a strong overall design statement. A detail comes to mind, namely: the very peaky treatment of the sharply raised fender as it met with the A pillar. Nothing was there just to be there, it all had a purpose.

Then came the three-door version, since a dedicated coupé body could not be funded. For this variant, Stéphan came up with an absolute scorcher: The gall of the man! He kept the carried-over upright rear end, introducing an almost geometrical swoop to the rear side window that ignored the roof - or did it? I fell in love with this solution and thereupon took it upon myself to sell that design as is, exactly like the sketch - and nothing less. I later drove the RS version and I’ve never been so proud to have such a car on my drive way.

Once more, it is proven that to capable designers, restrictions act as challenges, rather than obstacles. That a look as uncompromising as the three-door Mégane II’s was the result of a combination of necessity and creativity speaks volumes in this regard - highlighting this car’s special role as a functional statement design.

Of course, design is not the work of a solitary genius. Many can claim to have had a major responsibility for what was to become a landmark design. There was that inspiring, yet unrefined sketch, drawn by Florian Thiercelin, the designer of the Vel Satis concept car, which led to a beautifully sculpted body that would not have seen the light of day without the truly inspired talent of Advanced Design director, Michel Jardin. Before that, there had been all those who had thought, researched and debated, in order to establish a design philosophy, before drawing a strategy and sharing it throughout the company. And what of all those efforts put into the negotiated advancements, step by step, with our engineering colleagues, in order to pursue what we had identified as the Fundamentals of Good Design. Then there was the human touch of Antony Grade, the man in charge of the overall automobile design operation. Not to mention those two remarkable ladies, the double As, Anne and Agneta: Energetic Anne Asensio, who held the position of Design director of the C Segment, and our pocket-sized Swede, the engineering-trained Agneta Dahlgren, Mégane II’s project leader. They both fought tooth and nail for every detail on that car, be it the exterior, as well as the interior design which, by the way, was designed by a street cycling poet named Udo Hischke. Given it would take a brave group of engineers to face the well-prepared arguments of our double As, I’m glad they were on our side!

Then there was our visionary president, Louis Schweitzer, who would later say that what he enjoyed most about his presidency was his visits to the Design Center.

Not finally, but additionally, I’d like to say that we had the most design-driven programme director that I have had the pleasure to encounter in Carlos Tavares, who accompanied us whenever a troublesome item had to be crossed off the agenda. He was there, with us, with Design. Carlos Tavares clearly needs little introduction, as he now leads the Stellantis Group. Probably everyone already knows that he is a true auto enthusiast and very active in motorsports.

Personally, I don’t race cars. But I was there, too.

Click here for ‘The Surge’ Part VI

Image credits: Patrick le Quément archives, Renault

Car interior designer who created some of the most significant cabins of all time, most notably the Porsche 928’s