The Surge (IV) - The Wall

Good car design expresses a mindset - hence the need for Patrick le Quément to win over hearts and minds, ahead of the Renault Mégane Mk II’s creation, as laid out in this candid account, created in conjunction with Christopher Butt

Curiosity may be the defining creative trait of Patrick le Quément’s. His tenure at Renault Design accordingly was about an ongoing quest, rather than a final destination. Hence the Senior Vice President Design and his team envisaging the brand’s style to be guided by an ethos, rather than a set of styling cues. However, defining that ethos was a considerable challenge in itself.

The least expected discoveries that we made with our designers was that the non-French team members seemed to be the greatest supporters of our quest to find a unique positioning for Renault through Frenchness. For those whom we had hired came not only to join Renault, but also to live in Paris, under the spell of the dialectical baguette that ruled us all, as well as the promise of a stroll on the Champs Elysée, the peeling red paint on the café signs, or the bewitching smell of fresh bread from the Boulangerie, which all resulted in a charm that made everything seem right, seem… charming.

On the other hand, quite a few of the French designers, particularly those that had a long past with the company did not really understand what we were aiming for. It was akin to the story I’ve regularly told of the man walking along the bank of a stream, on a scorcher of a day, who wonders if he can take a dip in the river to cool down, but is uncertain regarding the water’s temperature. Seeing a fish swimming along the bank, he asks the fish: «Hey fish, how’s the water?» To which the fish replies: «Water, what water?»

The Vel Satis and Avantime concept cars may have laid the stylistic groundwork for Mégane II, but they only truly proved that sound ideas were in place - how these ideas were to be implemented was an altogether different, crucial issue. As history has taught, time and again, the best ideas are worth nought if they remain theoretical - or are critically diluted.

There was something that all designers, be they French or coming from any other nation, agreed upon, however: that Renault Engineering had to engage in their own cultural revolution. For if Renault were outstanding in their creativity, when it came to developing a new concept, they were simply far removed from world’s best standards when it came to inventing an attractive vehicle package, such as Audi would come up with, time after time.

In those days, Renault’s engineers were in the hands of three schools of Engineering: the Arts & Métiers, the Central School or, if one was dealing with the true élite, the Ecole Polytechnique. About the latter’s graduates, the following was regularly claimed: «They know everything, and nothing else». And so it was that I came into this company, as a mere stylist - even if I had a diploma in Industrial Design, as well as an MBA. To these engineers’ eyes, I was just an artist and therefore close to a manual worker, and clearly not one cut to think strategically.

It was the arrogance of a few of its leaders, «them from the old school» that particularly irritated me. The ones who had criticised American cars’ handling, when they ran American Motors, as being like a bar of soap in a bidet. That same bunch who, at the when time «Le Style» still reported to Engineering, had described to a journalist that the role of stylists was to dress up the hunchback.

The newly created Renault Design accordingly faced The Wall, a fortress with no door. However, just a year after my arrival in Renault, Président Lévy, himself an alumnus from the École Polytechnique, appointed me to head a multidisciplinary team to tackle the mammoth task of drastically reducing the company’s «Time to Market», as our program developments were significantly longer than best practice. That did indispose the technical community and later, when his successor appointed me head of the cross-company Delta group to push through some of the changes that the MIT’s study recommended in order to implement Lean Manufacturing into the company’s operations… silence fell upon the Engineering senior echelons. This was then followed by absolute stupefaction when, in 1995, I was appointed Senior Vice President of Corporate Quality as well as Design, joining the company’s board, answering directly to the Président.

That certainly caused another stir, leading to The Wall beginning to show furtive cracks at the same time as a tiny door was eventually pierced through it. This was largely due to the newly appointed head of Product Development, a former Michelin man, and - of course - another alumnus of the École Polytechnique: Carlos Ghosn.

The new master condemned all the various engineering departments for suffering from acute silo syndromes, requesting all the walls to be torn down. They certainly were in due course, but then, the new ruler used all the disassembled stones to erect a huge fortification all the way round his property, allowing only a draw bridge to be built. The message was clear: the Product Development Group was one, and there was only one door which led to the boss. On which I knocked immediately.

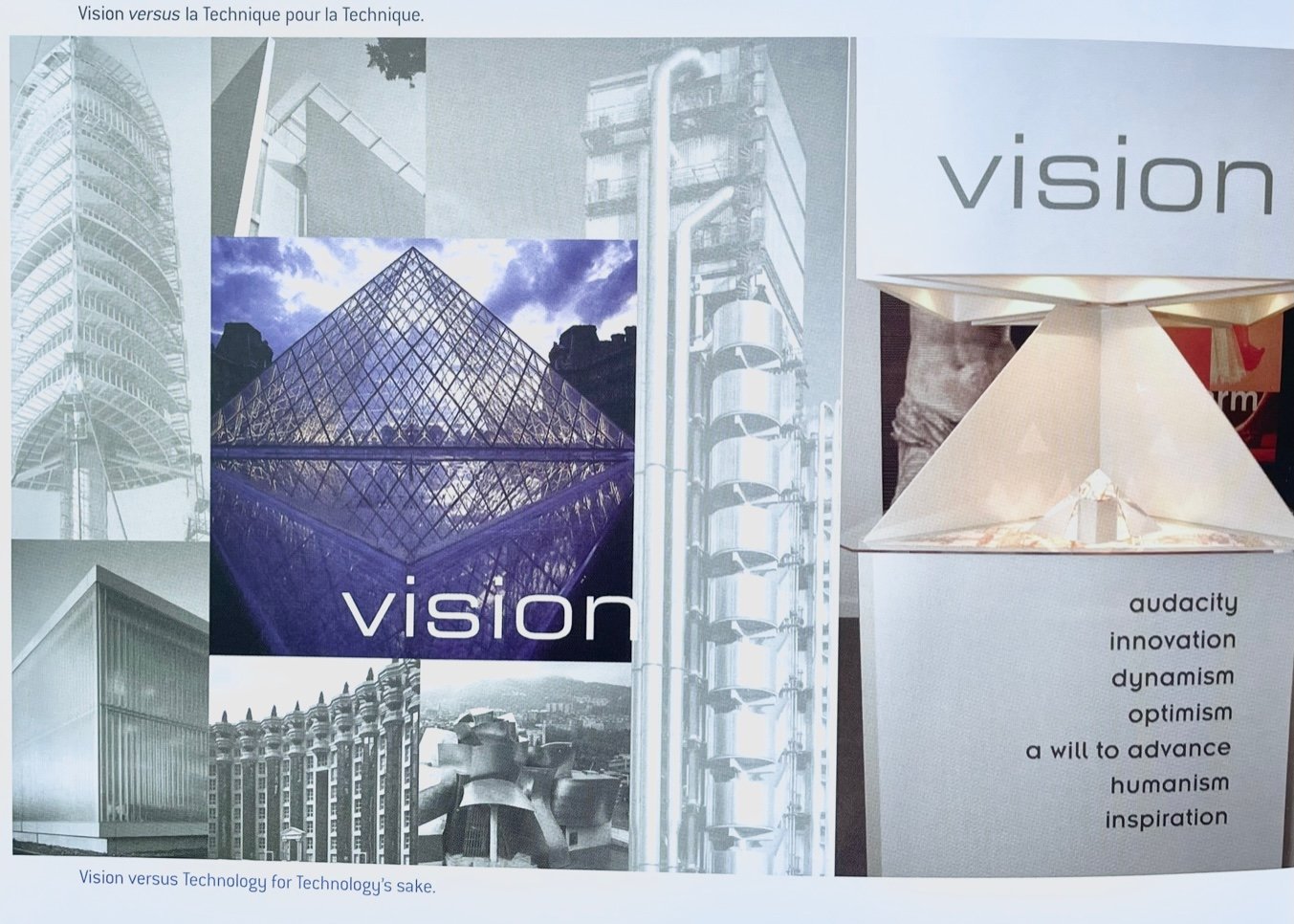

This was the time when we published our first edition of a thoroughly prepared booklet titled The Fundamentals of Good Design, which assembled all the themes that we had, for the most part, already engaged with the different parties - with varying degrees of success. It became an official agenda with our colleagues from Engineering, with Product Planners quickly joining in. It tackled issues like lateral overhang, front and rear overhang, tumble home, wheel size, vehicle attitude, proportions & stance, visibility, aerodynamic aspects and integration, countenance & anthropomorphism, openings and, written in capital letters: PERCEIVED QUALITY. But that was not all - interior design was also very much on the agenda, with themes such as exterior/interior consistency, vehicle architecture and interior space, Touch Design and Simplexity, integration, dashboard, seats, loading, stowage features, colour and trim, atmosphere and lighting, shared experience and again PERCEIVED QUALITY.

Among the gifts the ‘90s gave to automotive design - the monobox and retro design also being among them -, perceived quality turned out to be the most influential. Rather than being a side effect of high-quality components, the way any button, handle or piece of trim looked and felt became an end in itself. It marked a true sea change, whose effects are only gradually abating, as focus shifts towards conveying superiority through digital means.

These were all the areas that needed to be tackled with great urgency. Areas of study that we had already idealised on our vanguard programme of concept cars, our rolling manifestos. Concept cars had made some of those responsible of our production cars look away with a detached disdain, with claims of them being unrealistic and costly toys - but Carlos Ghosn took them very seriously. Among the younger generation of engineers and many, many product planners who were more open to the outside world, it was agreed that there was much to do - which they took on in due course.

Amongst these professionals, another Carlos emerged: Carlos Tavares, who at the age of 41 was appointed Programme Director of the Mégane II.

With the complete team in place, we could set to work!

Click here for ‘The Surge’ Part V

Image credits: Patrick le Quément archives, Renault

Car interior designer who created some of the most significant cabins of all time, most notably the Porsche 928’s