The Surge (I) - Eureka

In this series of uniquely candid articles, car design maestro, Patrick le Quément, and DFT's editor, Christopher Butt, jointly cover the creation of the one of the very few mass-market landmark designs, the Renault Mégane Mk2, offering unparalleled insights

Received wisdom suggests that bold landmark car design is, almost by definition, restricted to niche models. Mould-breakers such as the Audi TT, Renault Twingo, Mercedes CLS or the Nissan Cube would lend this argument some credibility, given these were all-new models, without a clearly defined market of potential repeat customers whose expectations ought to be met, no matter what.

And then there is the second-generation Renault Mégane. A car literally made for the masses, a car that most decidedly did not follow in the footsteps of its successful predecessor. A car that, were it not for its ubiquity, would turn heads even today, in ways usually reserved to exotica.

The Mégane II is a marvel whose magic we have become accustomed to. Unfairly, its success prevents it from the kind of retrospective adulation rare landmark car designs are regularly bestowed with.

Given the creative inhibitions present in so much of today’s automotive design, now would be as good as any other time to revisit a car embodying the power of creativity like few others - also with regards to its success, which proved that it can pay off to positively challenge customers, after all.

Rather than a mere reappraisal, this series of articles tells the story of how this most eclectic compact car came into being, from the perspective of none other than Mégane II’s spiritus rector, former Renault Senior Vice President Design, Patrick le Quément.

As with most successful corporate creative endeavours, the tale of Mégane II begins far earlier than one would expect, involving an eclectic combination of lightning caught in a bottle and protracted elaboration.

There it was, pinned to the half-sized presentation board, just before reaching the corridor. A half-sized sketch, seemingly predestined for the «salon des refusés» - or salon of rejects -, in reference to all those marvellous impressionists whose paintings were thought of as too awful to be hung at the official Paris Salon in 1863.

There it was, catching my eye, just as I was about to leave the Advanced Design studio, where a presentation had taken place to select a design theme for our future Z09 concept car, whose mission was to symbolise the first 100 years of Renault. This gathering had lasted more than an hour, as we meandered back and forth, debating amongst ourselves the merits of the different proposals that were pinned onto four large display boards. I felt somewhat despondent, as I had not seen any theme that corresponded to our design brief. For even though I hardly ever participated in exploratory design meetings with an image already engraved in my mind - favouring by far painter Pierre Soulages’s approach on inspiration, which he described as «what I find tells me what I am searching for» - this time as I was taking leave of the assembled group of designers, going back to my office in a sombre mood.

That moment, my eyes fell upon this little sketch. A simple sketch to be sure, and yet not a scribble, as it was all there, all the essential lines to create a singular and powerful design statement. I instantly recognised who was the author of that drawing: it could only be that of Florian Thiercellin, a soft spoken thinking man, who was never to be found in the front row, preferring the reassurance of being at the back of the group. Once again Florian had come up with the answer. He had imagined something completely original, a shape that expressed a certain futurism with it’s raked windshield one box silhouette, and a rear end that took its inspiration in the flamboyance that characterised pre-war French carrossier and master of elegance: George Paulin.

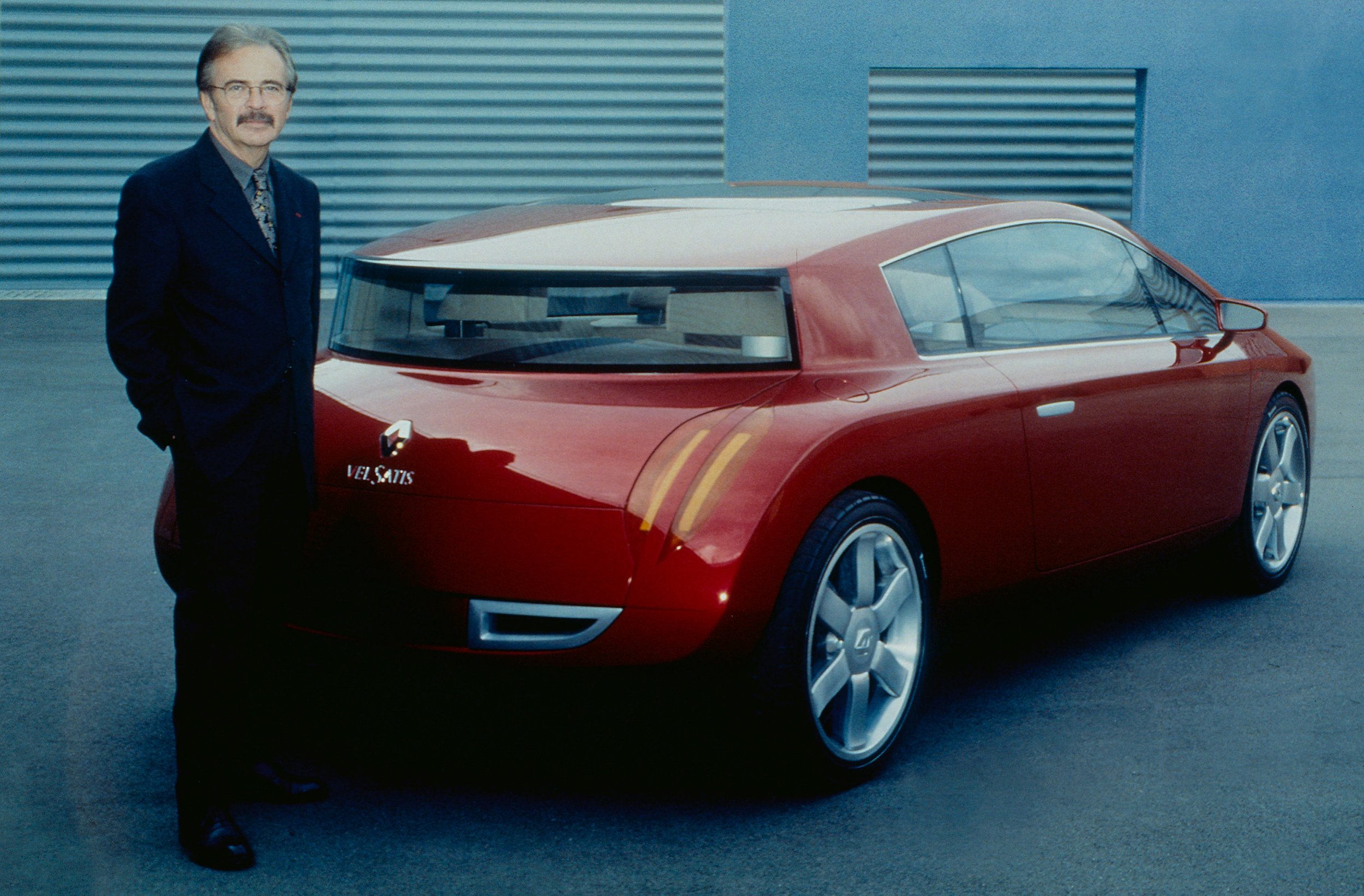

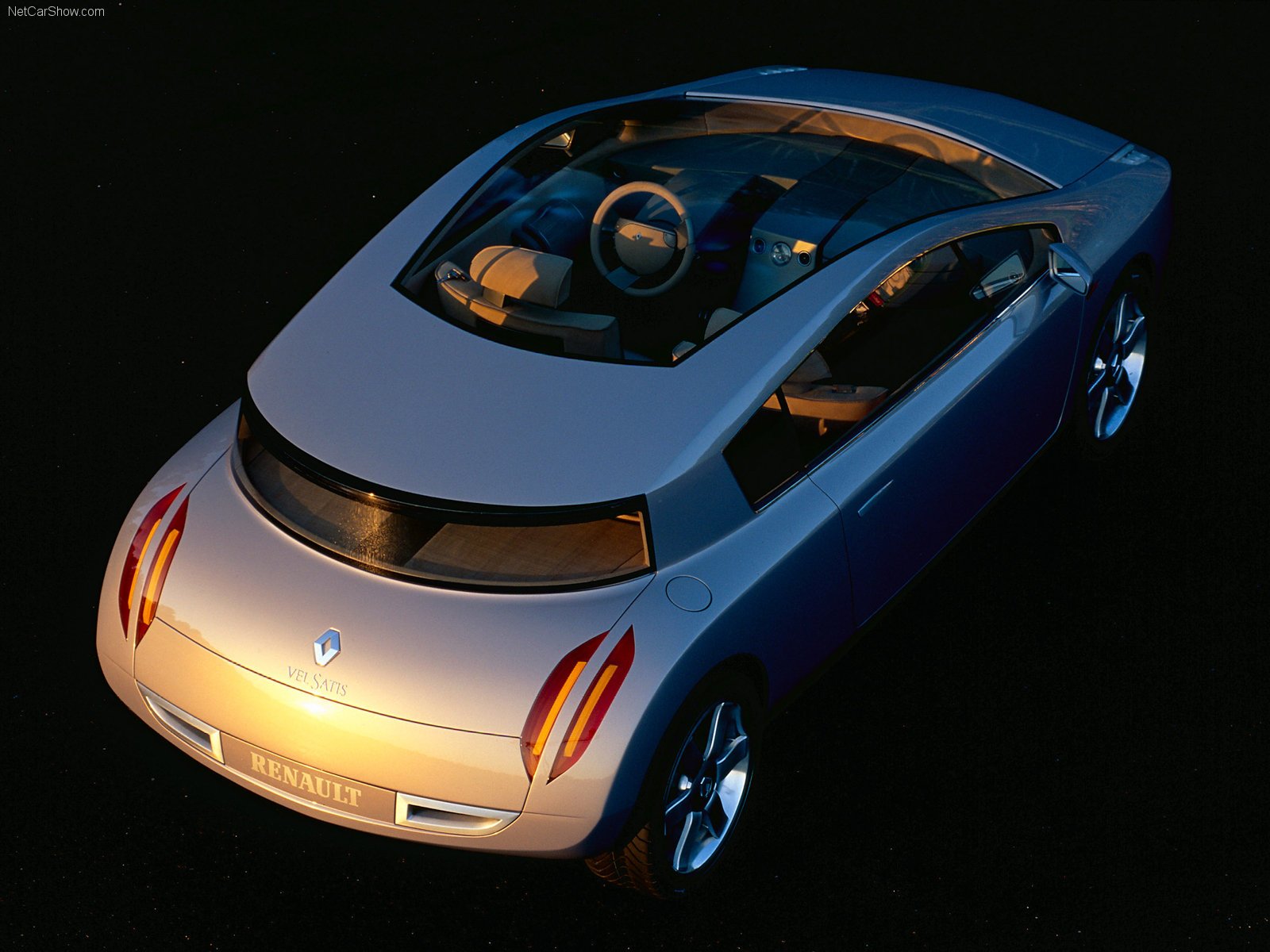

Florian Thiercellin, Renault Design’s most enigmatic presence. An unusual designer, judging by his delicate sketching style alone, whose contributions to Renault design were considerable - what with Thiercellin having penned the exteriors not only of the Z09, but also the earlier Initiale and, for better or worse, the Vel Satis production car.

It must be assumed that someone of Thiercellin’s calibre could get overlooked all too easily. Universally described as an exceedingly shy character - albeit with arrogant tendencies, according to some -, a withdrawn creative such as him would usually find it hard receive attention in an industry all too often fostering self-promoters. Yet at Renault Design during the ‘90s, Thiercellin (who, by the way, still calls Technocentre his workplace) was allowed to leave his indelible mark on Renault and French car design.

We had given our designers a very precise, yet open brief for the Z09 concept car that was to be known as Vel Satis: our objective was that it should be a coupé par excellence to celebrate the 100th anniversary of Renault. Then again, it should also reflect two phases of Renault Design’s strategy. The first such phase had begun in 1988 and lasted all of seven years. It was aimed at re-establishing the image of Renault as an inventive and creative company once again, in line with the assignment I had negotiated with President Raymond Lévy when he hired me. The fruits of these efforts being our concept and production cars like Scenic, Argos, as well as Twingo.

The second phase of our design strategy we entered in 1995, conscious that, despite our commercial successes, we had to focus our attention on the development of a stronger and more specific identity for all the future models of our range. And this could only be done through the catalyst that concept cars were in our design strategy. Vel Satis was destined to flavour all our future models as a dollop of garlic butter does to all the ingredients assembled in a hot sauce pan.

This move would seem to address the one weakness of those first-phase Renault designs. Laguna, Mégane I, Espace III and especially Twingo each exhibited a distinct flair of their own. But for all their creative and commercial success, they stood more for themselves than adding up to an overarching Renault theme. In distinct contrast, the second-phase Renault designs would work both as stand-alone designs and in the context of the brand.

Our Z09 concept car was developed in Turin, which I favoured as it not only allowed us to use the remarkable craftsmanship of the G-Studio workshops, but also almost excluded any outside interference.

When the Vel Satis concept car was first presented to the president, he just fell in love with its freshness. This was followed by a rapturous welcome by the general public at the 1998 Paris Motor Show, as well as the design world at large - and, to some extent, even some members of the press.

Mission accomplished? No, not really. The next phase was yet to begin.

Click here for ‘The Surge’ Part II

Image credits: Patrick le Quément archives, Renault

Car interior designer who created some of the most significant cabins of all time, most notably the Porsche 928’s