In Memoriam: Hans Braun

Car interior designer who created some of the most significant cabins of all time, most notably the Porsche 928’s

Hans Braun at work in Weissach

To claim that Hans Braun’s fame was in inverse relationship to his success as an automotive designer would constitute no hyperbole. It would be a mere matter of fact. For even within the car design community, his (admittedly common-or-garden) name rings bells on a highly irregular basis only. His work, by contrast, would have any design professionals and aficionados worth their salt immediately gushing with praise.

With regards to his absence of fame, Braun’s crucial mistake was the choice of his domain: interior design. Best described as «selfless, shy blue collar bees that work long and lonely days without being noticed, getting their own pleasure in the complexity of the interior universe», interior designers are almost inherently discreet. The pleasure they take in their work, instead of some latent or blatant longing for public adulation, at best results in pieces of design that satisfy the user through ingenious practicality and please the aesthete, courtesy of elegant solutions to challenging requirements.

Whereas a car’s exterior design aims for visceral impact, interior design is an intellectual craft. An exterior can be forgiven most practical drawbacks if it is beautiful. An interior that does not fulfil its purpose is an unreserved failure. Accordingly, good interior design commands respect, instead of igniting passion.

This certainly was the case with Hans Braun’s two most famous pieces of work, the seminal interiors of the Porsche 928 and the BMW E30. The former achieved no less than the setting of a new standard for the craft, whereas the latter played a crucial part in the fundamental establishment of a brand through design. In either case, aesthetics went hand-in-hand not only with function, but a strong narrative that allowed both the Porsche and BMW brands to evolve.

As with so many legends of automotive design, Rhineland-born Hans Braun received no formal training. A lifelong car fanatic, Braun was initially trained as a decorator at Kaufhof department store in post-war Cologne, refining his illustrations skills during his time off and indulging in his passion for racing each weekend. In that latter context, he eventually came across Ford of Europe’s Uwe Bahnsen (another trained decorator, incidentally), who offered Braun a job interview at the Merkenich studio in 1961. The rest is history - as well as a telling tale of what passion, talent and determination could achieve within an automotive design industry in its prime.

His first years as a designer taught Braun the tricks of the trade and presented him with a first opportunity to concern himself with a design concept that would play a major role in his later career, but was to remain merely an experiment at Ford: the driver-oriented cockpit. After hours, Braun would continue his racing exploits, eventually also as part of Ford’s works team, alongside the likes of Jochen Neerpasch and Bob Bondurand.

Braun’s passion for fast driving was to inform his work to a much greater extent from 1968 onwards, when he moved from Ford in Cologne to Porsche in Stuttgart-Zuffenhausen. Initially working under Heinrich Klie and then incoming chief designer, Tony Lapine, Braun quickly established himself as an authority in the interior design field. As such, he was part of the team tasked with turning around the fortunes of project EA 266. The Porsche-developed, Ferdinand Piëch-engineered Beetle successor’s ungainly appearance had been among the reasons for the hiring of Lapine and the team of trusted creatives and craftsmen the new chief designer had brought along from his previous post at Opel. This Rüsselsheim Gang and Hans Braun put EA 266 into turnaround, changing the ‘telephone booth’ into a comely, modern compact car, inside and out. Braun’s contribution had been a sleek, minimalist dashboard that was conspicuously more visually cutting-edge than any VW cabin design from the years prior - or the upcoming decade, for that matter.

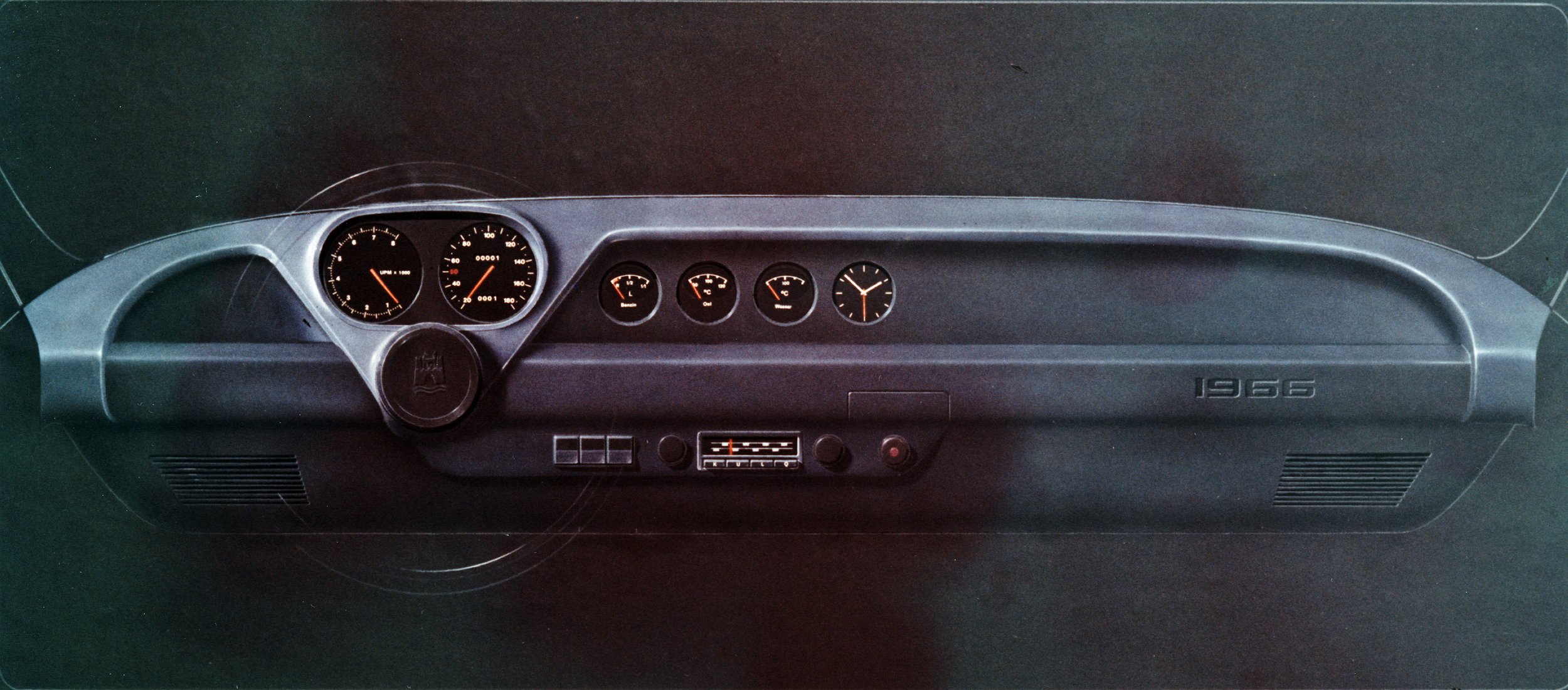

VW EA 266 dashboard by Hans Braun

Unlike EA 266’s cabin, which was to remain a secret outside Porsche (owing to the entire project’s spectacular, embarrassing last-minute cancellation), Braun’s ensuing VW design, for the EA 425 sports car, was put into production, albeit under the name of Porsche 924. Sharing the EA 266 dashboard’s symmetry, but in a far more conventional, cliff-faced variation, in hindsight the 924’s cockpit was Braun’s most conventional piece of work.

Dick Söderberg, Anatole Lapine, Hans Braun, Wolfgang Möbius

The same could not be said about the masterpiece he was working on simultaneously. Like all other aspects of the Porsche 928, its cabin was intended to be sophisticated and groundbreaking at once. Consequently, Hans Braun could pursue his ergonomic and aesthetic ideals with barely any concern for cost or complexity and created a strikingly coherent modernist environment, whose visual impact matched that of Wolfgang Möbius’ & Peter Reisinger’s sheet metal to a t.

Porsche 928 cockpit sketches by Hans Braun

With its slanted centre console (paid homage to recently in the Taycan), striking symmetry, adjustable instrument cluster and unerring attention to detail, the 928 cockpit bore little resemblance to a 1970s car interior. Wide panel gaps and the absence of digital displays notwithstanding, it could be perceived as a strikingly modernist environment, even today.

In the wake of such a tour de force, Hans Braun and the rest of Style Porsche’s staff were eventually confronted with the realisation that no creative challenges on even remotely similar a scope were on Weissach’s horizon. Rather than facing years of tinkering with existing designs, Braun hence chose to actively pursue new challenges and joined BMW in 1976. Alongside incoming chief designer, Claus Luthe, Braun would leave an even deeper imprint on the Bavarian marque than Porsche over the following years.

BMW interior sketch by Hans Braun

Despite not being as visually spectacular as his 928 interior, Braun’s design for the BMW E30 Dreier’s cabin would prove to be far more influential to the brand than the singular 928, serving as blueprint for two decades of BMW cockpits. The driver-oriented centre console not provided a definite take on an existing BMW trademark, but tied in with some of the ergonomic concepts Braun had pursued at Ford.

In addition to the many aspects of E30’s cabin that would serve as reference for future BMW interiors, Braun also created a specific component that would find its way into several dashboards: the drum air vent. A signature feature Braun himself also incorporated into his designs for the E32 Siebener and E34 Fünfer dashboards, it came to stand for BMW in a way similar to the red illumination of instruments or the ‘swan neck’ gear stick. Once Opel fitted an adapted version to its Corsa B, however, BMW felt compelled to abandon the drum air vent, after one last appearance inside the Z3 roadster.

The final BMW interior Hans Braun would work on in a hands-on manner was the E31 Achter’s, whose design was a collaborative effort with Karin Steinbach. In certain ways, the 8 series’ cockpit evolved some of the 928’s concepts, such as the slanted centre console, the instrument pod and the door-handles-cum-arm-rest in line with the dashboard. But the increase in sophistication of materials could not make up for the loss of conceptual purity.

During the same period, Hans Braun also oversaw the development of Wolfgang Wirtz’ concept for the E36 Dreier into the production design, as executed by Thomas Plath. A rare nod to prevailing trends, the E36 cockpit followed the fashion at the time for cliff-faced, driver-oriented dashboard architecture, as also seen inside the Golf Mk3 and others. With the ensuing designs for E38 & 39, penned by his future successor, Michael Ninic, Braun’s interior design department returned to the ‘80s cars’ basic architecture, albeit with materials of greatly improved perceived quality.

In addition to his duties as interior chief designer, Hans Braun also stepped into the breach when Claus Luthe had to vacate his post, in the wake of a personal tragedy. Braun pledged to oversee BMW’s design department for the time it would take to find a successor for Luthe, never intending nor inducing his promotion to be permanent. When Christopher E Bangle eventually was appointed BMW chief designer in 1992, Braun soon entered early retirement.

Among his Porsche peers, Hans Braun remains as well remembered for his awe-inspiring skills at the helm of early 911s (slid roads around Weissach being regularly exploited for long, fast, controlled drifting) as for his calm, composed bearing and flawless work ethic. At BMW, his extensive collection of Ferrari F1 race car scale models (one of each season’s car, since 1953) is referenced almost as regularly as the legacy of his work.

To design cognoscenti, Hans Braun ought to be remembered as a reticent maestro, whose creations are not merely pleasing to look at, but deeply satisfying to use.

Hans Braun

(* May 29th, 1935 - † November 5th, 2021)

Image credit: BMW AG, BMW Group Classic, Porsche AG

Car interior designer who created some of the most significant cabins of all time, most notably the Porsche 928’s