Measure Of Success (I)

Creative success is fiendishly difficult to gauge - yet there is one measure that is more telling than the others, according to Christopher Butt

Automotive design is no science.

Accordingly, to try and measure its success is a task so fraught with limitations, the result cannot be anything but pseudo-scientific. After all, neither sales figures, nor application of the golden section (or lack thereof) can ever tell the whole story.

Only when taking commercial, as well as social and artistic factors into account, does one utterly non-scientific, yet creatively significant measurement come to the fore: pop cultural relevance. Or, in other words: the meaning attributed to an automotive shape. The success at either resembling or driving the Zeitgeist.

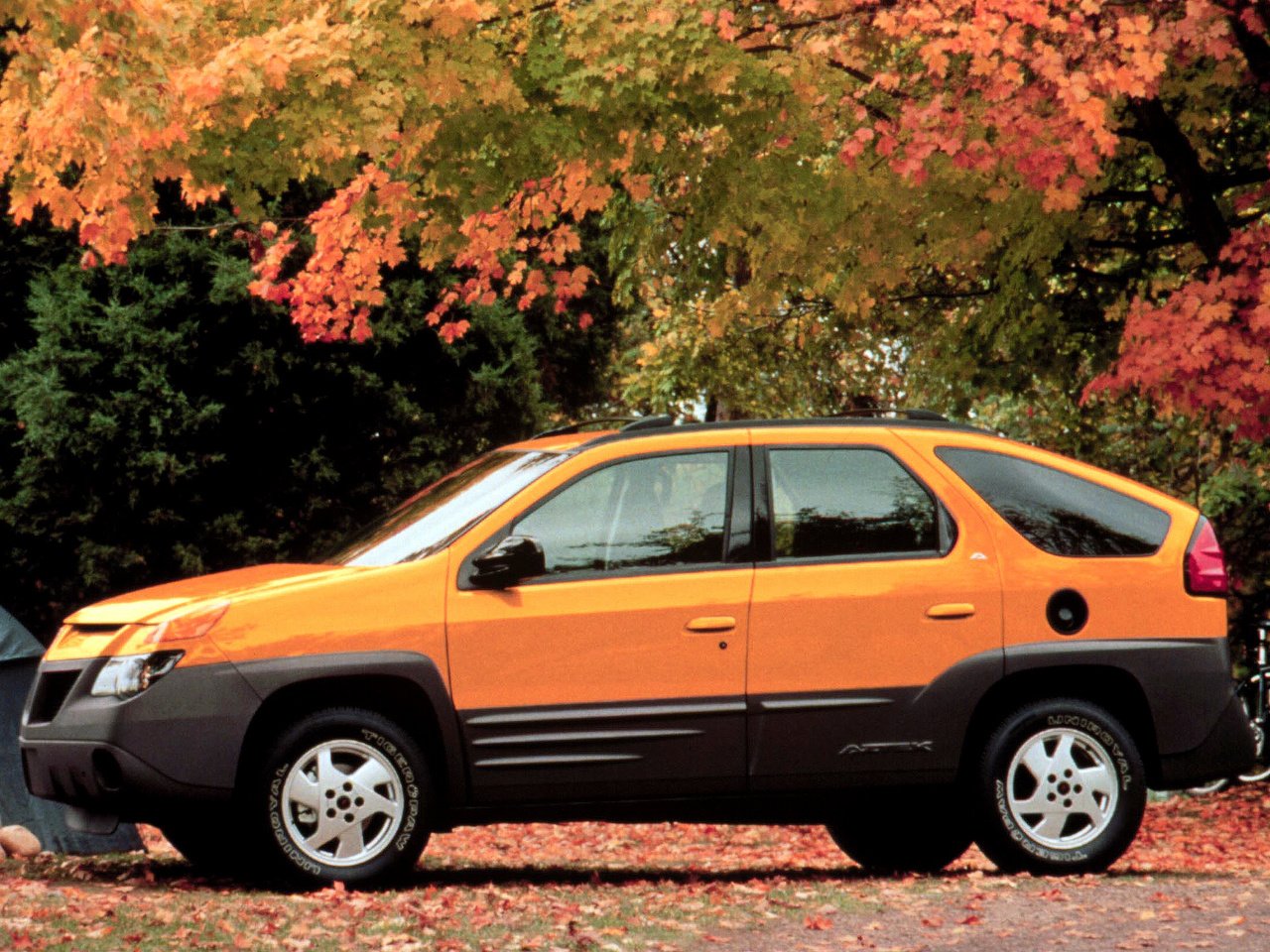

To get the greatest misunderstanding out the way, two of the great icons of automotive pop culture must be mentioned right away: The Aston Martin DB5 and the Pontiac Aztek. Both owe their elevated status to product placement, rather than the strength of their design. The Aston’s shape was already ageing when Sean Connery sat down behind its steering wheel for the first time. The Pontiac was a car sub-culture in-joke, until Vince Gilligan et al decided to let Breaking Bad’s viewers in on it.

Both Bond’s and Walter White’s cars gained pop cultural relevance only by association. Their effects on automotive design in general have accordingly been limited (DB5) to non-existent (Aztek) - unlike, in no particular order, the original Ford Mustang, VW Golf MkIV, Mercedes W126 S-class, Lamborghini Countach, Fiat Panda, Renault Twingo, Cadillac Escalade, Audi TT, Jaguar E-type and several others.

Pop cultural relevance cannot be bought. It must be earned.

All great car design possessed this relevance to some degree, once more highlighting the (erstwhile?) role of the automobile as a canvas onto which societal and individual needs and desires are (used to be?) projected.

Retro design was the most obvious acknowledgement - and, indeed, exploitation - of this aspect. VW New Beetle, Mini R50, fifth-generation Mustang, Fiat 500 et al appropriated the pop cultural appeal of their successors to their own ends, in the most straightforward manner. Despite seemingly being straightforward remakes, these designs didn’t attempt to repeat history and aim for a similar effect as their archetypes. Instead, they conveyed a mutated, blatantly subjective take on the design they emulate. Hence the plucky, cheap Mini evolving on the basis of Rallye Monte Carlo wins and a handful of luxurious coachbuilt variants driven by the stars of its era, rather than its original efficient mobility for the masses ethos - what with Blair-era Cool Britons placing charm and flair rather higher on the specification sheet than a generation of drivers still acquainted with food and petrol rationing.

Whereas the Mini R50 coated a still relevant type of vehicle (the supermini) in nostalgic playfulness, the New Beetle basically attempted to rejuvenate an obsolete type of vehicle, courtesy of some postmodern quirks. While novel for a brief period - and well executed, in terms of styling craftsmanship - the Volkswagen was a one-trick pony. The Mini, for all the unfaithfulness to its mass-mobility roots, turned a perfectly worthwhile product (the supermini) into a desirable product, whose drawbacks (space inefficiency, ergonomics, price) were more than offset by its romantic appeal, or, in other words: its genuine pop cultural relevance.

Two decades later, with the passive-aggressive SUV in its various guises dominating the automotive Zeitgeist, the appeal of the Mini’s and Fiat 500’s romantic shapes hasn’t diminished - to the contrary. Yet neither retro design, nor any SUV embody the most pop culturally relevant trend in car design, anno 2022.

For the current industry hot spot is not located in either Shanghai, LA or Munich, but Hwaseong, South Korea.

To be continued…

Image credits: Aston Martin, Audi AG, BMW AG, Fiat Auto, GM, Renault, Volkswagen AG

Car interior designer who created some of the most significant cabins of all time, most notably the Porsche 928’s